Could HR Tech save America’s public schools before it’s too late?

-

- Hundreds of thousands of teachers leave the profession each year, costing the government an estimated 2.2 billion dollars annually.

-

- Enrollment in teaching programs has dropped 10 percent since 2005.

-

- Teachers cite negative work culture as primary reasons for leaving.

- The US is no longer among top-performing countries on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA).

“We’re not leaving!” shouted thousands of educators occupying the Oklahoma state capitol building. It was the second day of a statewide teacher walkout, one that would inspire similar protests across the southwestern United States in the following months. Punctuated by rhythmic clapping, the chant on April 2nd held an uncomfortable irony, however, in that teachers are leaving. And in droves.

The exodus of certified K-12 teachers in the US – at a rate of about eight percent annually – has become as much of a back-to-school routine as buying a new backpack. And though the teachers’ nationwide median attrition rate – twice that of Finland and Ontario, Canada – makes the news cycle for a brief moment every autumn, the root causes have yet to be adequately addressed.

“We’re set to fail from the beginning,” says Jocelyn Good, a second-grade teacher in Northern Illinois with five years’ experience, “with countless assessments assigned without the tools, time, or support to reach the expected goals.”

While Good says she plans to carry on into her sixth year and beyond, about 40 percent of American K-12 teachers won’t make it past year five.

“I wish people had an idea of what it’s really like on a daily basis,” reflects a former high-school teacher from eastern Washington. She asked to remain anonymous, so let’s call her Joanne. “I can think of no other job scrutinized to the same extent, and with very little support from the system it serves,” she says. “After two years I decided I couldn’t continue in a classroom full-time, simply because of the bureaucracy and nonsense involved.”

Now a high-school, college, and career specialist focused on working with high school students from low-income and first-generation families, Joanne recalls the constant pressure to prove one’s worth, often through required courses, to be paid for, out of pocket, by the teacher. She’d look at her acquaintances outside of teaching; people, like herself, graduates of four-year university programs and certified experts in their fields. These people seemed to be treated with respect and valued by their employers. Joanne’s husband for instance, an engineer, never had to foot the bill for government-mandated continued-learning courses, or purchase supplies for his employer with his own money.

Teacher attrition costs American public schools about 2.2 billion annually. To replace one teacher in an urban school district costs around $20,000 in recruitment and training alone, not to mention the emotional toll the constant turnover takes on the staff.

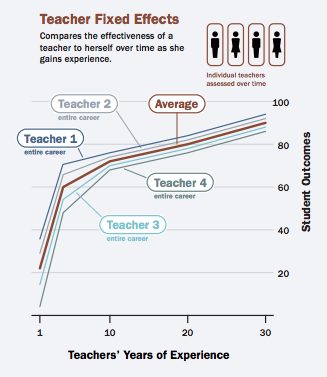

The Learning Policy Institute found that students perform better, and log fewer absences when instructed by an experienced teacher. Not only that, but new teachers perform better when they have more experienced colleagues. And yet, as of last September, 100,000 classrooms across the country were staffed with an under-qualified educator.

So how much experience is enough? The same Learning Policy Institute report indicates student gains are most significant in a teacher’s first three years, but continue to grow steadily over their career.

Thus far, the overwhelming response to the teacher shortage has been reactionary. US schools have started hiring from the Philippines, or alternatively-qualified teachers nearby, just to fill the gaps. While the hustle is laudable, it’s not a solution. Most of the foreign teachers aren’t eligible for long-term visas, and uncertified instructors are 25 percent more likely to leave. Schools stop-gapping like this are bound to find themselves in the same position the following year, only worse.

It’s not entirely low pay that’s pushing educators out of the profession. Though teachers make an average of 11.1 percent less than their peers in other industries (up from two percent in 1995), The Learning Policy Institute lists compensation as fourth on the list of why teachers quit, behind inadequate preparation (as in teachers who are uncertified or inadequately trained), lack of support for new teachers, and adverse working conditions.

The tech industry has heard the distress call, and platforms for monitoring group interactions have been popping up everywhere, from Slack bots that flag microaggressions, to AI that susses out team dynamics. In fact, the Human Capital Management market, as a whole, is forecasted to grow by almost thirty percent in the next five years, from $14.50 billion in 2017 to $21.51 billion in 2022.

“We are in a really interesting era for workplace culture, how it’s defined, and how it’s managed,” says Sarah Wilson, head of people for SmartRecruiters. “Technology has replaced so much of the ‘technical’ job requirements in so many industries that we are now, more than ever, relying on personal values and empathy as key attributes for success. As such, many companies (including ours) are spending time and energy in analyzing their company cultures and subcultures.”

Outside Topeka, Kansas, a district of just over 5,000 students is making great strides.

Brian White, Executive Director of Human Resources and Operations in Auburn-Washburn for the last six years, decided it was time for a change, so he switched their legacy applicant tracking software to SmartRecruiters a little over a year ago.

“Statistically, I’ve increased my applicant flow,” he notes, “and anecdotally, I’ve received positive feedback from teachers, who say it’s much easier than other districts to which they apply. The teacher talent pool in the United States is shrinking, which makes recruiting teachers a more competitive process. You don’t want to create barriers to completing an application.”

That’s not to say candidates in their pipeline are any less vetted than other districts, it’s that the initial buy-in is easier. From that point, the recruiters ask what they need and when they need it, thus engaging the applicant without overwhelming them with asks.

“Last decade technology” is how White describes his district’s old ATS. “It wasn’t mobile-friendly, and the interface wasn’t intuitive or easy to us.”

That description is sadly emblematic of most tech in public schools, where clunky software makes applying for open positions more difficult than it needs to be, and on the recruiter side, outdated tech makes it hard to get input from teachers and stakeholders from within the school.

“In the education application process,” White continues, “you have to provide a lot of information up front. You’re asked to upload references, letters of recommendation, transcripts, evaluations, resume, and cover letters. It can take up to three hours, whereas our initial application takes 10, 15 minutes, max.”

Hiring well is an important first step to creating a culture of respect and trust between teachers and administration. A collaborative process ensures that veteran teachers feel their input is valued when it comes to the recruitment of new staff, and a positive candidate experience ensure that workers feel respected from the beginning.

“I think building a sense of community among the teachers would help,” says Jocelyn Good, of her experience entering the world of public schools. “When you’re new, coming into a building of teachers that have worked together, sometimes it’s hard to be welcomed and you can feel like you are alone and have no support.”

And community is precisely what’s next on the agenda for White. “We are already looking at different ways to engage in the communication process more,” he says. “Right now there’s a negative stigma on teaching. So we have a challenge to change that perception of education as a profession to something positive. Teaching is something you should want to get into.”

Hear more from Brian at Hiring Success 19 – Americas, February 26-27 in San Francisco. Check out last year’s highlights below!